Messages on Rails Part 2: Kafka

In the first part of this series, we were exploring some potential options for communication between services - what their advantages and disadvantages are, why HTTP API is not necessarily the best possible choice and suggesting that asynchronous messaging might be a better solution, using, e.g. RabbitMQ and Kafka. Let’s focus this time entirely on the latter.

What Is Kafka?

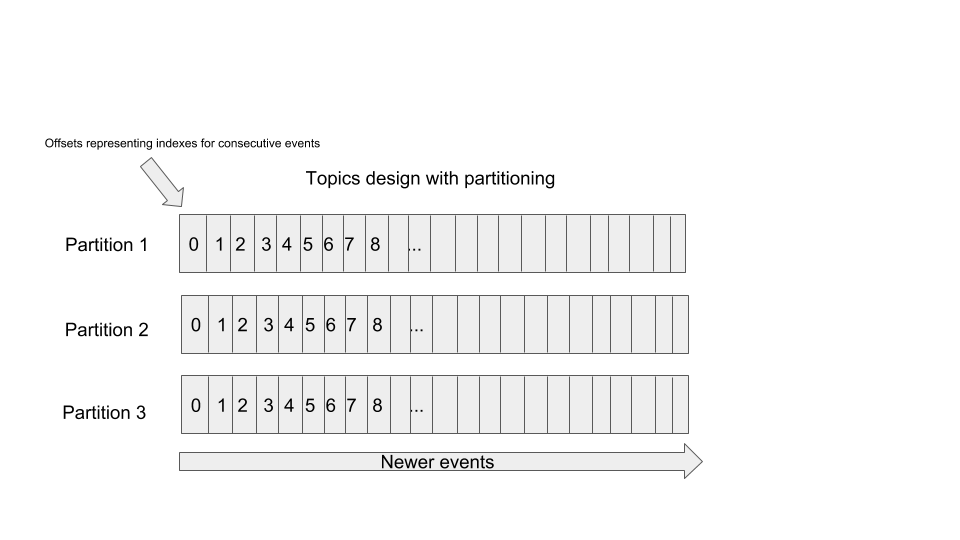

Kafka is a distributed streaming platform which allows the implementation of a publish-subscribe model between producers and consumers. However, what is unique about Kafka, is the fact that it’s somewhat closer to a storage system than a message queue. Unlike in a typical message queue, the messages are not removed once they are consumed, they are still kept there. But what exactly is that “there”? The events are stored in topics - the append-only logs in which messages are identified by “offsets”, which you could compare to array indexes. Topics can be split for parallelization by a specified key forming a partition.

What is more, a broker is not responsible for delivering the messages to the consumers - it is a responsibility of the consumer to make sure they consume the messages and keep track of the offsets so that they can read messages one by one.

There are notable side-effects of that design which gives a lot of options when it comes to taking advantage of Kafka. Since we deal with append-only logs, all the messages under a given partition in the topic are ordered. Also, as the messages are persistent and keeping track of the position in the log is on consumers, the events can be replayed by any consumer, including the new ones that have been just introduced to the ecosystem. When using a traditional message queue, there will be no way to access past messages when a new consumer joins, and you would need to do things like resending events manually or whatever else would make the most sense in that scenario, but with Kafka, this is something totally normal.

Since the messages are persisted, storage can become an issue on its own, What if our producers publish a massive number of events and we are not interested in keeping all of them, or we want to limit somehow the number of events that will be consumed by future consumers without actually losing anything important?

The first use case is quite simple - we may configure retention policy based on time (and, e.g., delete everything that is older than 30 days) or based on size (keep 1 TB of the logs). However, that might mean losing potentially valuable data.

That issue can be addressed differently, using log compaction. Imagine that you are publishing the projections of the models after each change to Kafka topics. If you are not interested in how exactly you ended up with having records in a particular state but only their latest state, there is clearly no need to store anything that happened before the last update. In that case, you can decide to compact logs by a given key achieving precisely that result. Moreover, you can also get rid of the message under a given key altogether - just send a message with the null payload for a specific key, and that’s it! No issues with storage and no need to consume messages in the future to figure out in the end that some record was deleted and a lot of processing went for nothing.

Modelling Kafka Topics

It seems like modeling topics shouldn’t be rocket science as we have limited options - we have topics where we can publish messages, and those topics can be parallelized by partitioning. However, this issue might be quite complex.

There are a couple of things that we need to take into consideration when designing topics:

- Messages are ordered within the same topic/partition

- The more partitions we have, the higher the throughput we can achieve

- The number of partitions per node has its limits which are determined by the number of file descriptors the operating system can handle since each partition is represented as a separate file. This value is configurable, yet, it is essential to keep that limit in mind and that you cannot increase it indefinitely, so having millions of partitions on a single node won’t work

- Also, more partitions increase latency

- The number of topics is limited in the same way as the number of partitions. In that sense, 10 000 topics with a single partition will not be that different from 1 topic with 10 000 partitions

A first idea that you might have in mind when designing topics is to have a topic per model, or generally speaking, a topic for events coming from the same model. That way, you might go with orders topic where you would publish events like order_created, order_completed, order_canceled etc.

There are several problems with that approach though. What if you have an event-driven system, where a consumer immediately acts on the data it receives? Let’s say that you have invoicing microservice that sends invoices to customers upon order_completed events. Obviously, besides the data from orders, it requires the data from customers. What if a customer changes the shipping addresses just before the completion of the order (resulting in publishing customer_shipping_address_updated event), yet, the order_completed event was processed before since the messages are published to different topics and they get processed independently? It might be the case that the address on the invoice will be incorrect! You might protect yourself against this kind of issues by assuming eventual consistency and, e.g., not acting on order_completed immediately but waiting 5 minutes instead, but this is not a solution that will work in all the cases and sometimes the cost of having issues like that might be too big, and you just can’t afford this.

In such case, if ordering matters, it is a better idea to publish events coming from different models to the same topic (and to the same partition!). In general, we can say that things that are needed together (order with their items and customer data) belong to the same topic/partition.

What if different consumers have different needs as far as ordering goes and what things should go together? It is a more tricky scenario, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution, you would need to make some tradeoffs, either on a producer or consumer(s) side.

Let’s get back to our example and imagine that we have another service that is for some reason interested only in customers’ data. Such an application would clearly be interested in customer_shipping_address_updated events, but they don’t care at all about anything related to orders. That scenario is pretty simple as the solution might be just ignoring the events (i.e., doing nothing upon them) that the service is not interested in. However, what if that would mean ignoring 90% of the events from the topic? You may choose to publish the same kind of events to different topics, so that they are easier to consume by different consumers, so the extra overhead would be on the producer’s side. There is a possibility of different scenario: another service has even more strict requirements about the ordering of more kinds of events. The solution would be no different though - either we could publish events to another topic, or we could use the same one and let the other consumers ignore even more events.

There is one more possible scenario: what if order_completed and customer_shipping_address_updated are a result of the same request/transaction? In such case, we could have a single event, e.g., order_completed_with_customer_address_change that would have a more complex payload and later, that event could be decomposed to smaller ones like order_completed and customer_shipping_address_changed and published to separate topics using a stream processor. Maybe this is a bit contrived scenario, yet, it’s worth keeping in mind that decomposition of events may also be a viable option, which is a much better choice than publishing split events and trying to reconstruct the original one.

Stream Processing With KSQL/Apache Spark/Apache Storm/Apache Samza/Apache Flink, oh my!

Even if you are not deep into data science, you’ve probably heard about Hadoop, which is arguably a king of batch processing in a big data world. However, that is not necessarily the most optimal solution if you need an almost real-time data processing which ideally requires working with streams (or at least with micro-batches). And this is exactly what we have with Kafka! There is a wide range of tools that can work with Kafka easily that could be used for ETL (Extract, Transform, Load), Data Enrichment, Machine Learning, Interactive Analysis or even as an extra component of Event Sourcing (e.g., building projections of the models from all the streams of events). Depending on the use case and requirements (e.g. very low latency, ease of use), you could go with Kafka Streams, KSQL, Apache Spark, Apache Storm, Apache Samza, Apache Flink or yet another solution. The list is quite long, and each of these tools deserves a separate article which is out of the scope of this one. Yet, it’s good to be aware of how introducing Kafka opens the way to more possibilities that are data-oriented.

Building Example Producer and Consumer Apps With Karafka

Now, time for some practice! Let’s build an example producer/consumer app that produces and consumes some event. To keep the example simple, let’s just build a single application as it will be no different than having a producer and consumer as separation applications.

We are going to use karafka gem for that, which is a higher level framework that structures the way of producing and consuming events and allows to focus on the business logic instead of figuring out how to integrate Kafka with the rest of the application.

Getting Started

Let’s generate a new application:

rails new karafka_example

And add required gems to Gemile:

gem "waterdrop", git: "https://github.com/karafka/waterdrop.git", branch: "master"

gem "karafka", git: "https://github.com/karafka/karafka.git", branch: "master"

Besides “karafka” gem, we also have “waterdrop” gem which is a dependency required for publishing events.

Let’s run a generator for all the things we need from “karafka”:

bundle exec karafka install

That command should generate a couple of interesting files: karafka.rb in a root directory, app/consumers with application_consumer.rb file and app/responders directory with application_responder.rb file.

The first file is pretty much an initializer for Karafka application which is separated from Rails config and allows you to configure Karafka application and to draw routes, which is similar in terms of API as Rails application routes, but here, it’s for topics and consumers.

ApplicationConsumer class is what you would expect that class to be - a base class for consumers. The interface is quite straight-forward for basic use cases: we define consume instance method inside which we have available params or params_batch (if we enabled batch fetching for that topic) that give access to event’s payload. There are also some callbacks available for consumers which you can check in the docs.

ApplicationResponder is a base class for producers. Why “responder” then and not a producer? Mostly due to the fact that they are quite similar to responders that you might have used in controllers as far as the intention goes. Usually, inside a responder, you declare a topic that you want to have registered so that you can send and consume events from it. Next, you define respond instance method which takes a single argument which is the event payload. From that method, you call respond_with method where you can provide topic name, a payload of the event and optionally, a partition key.

Initializer

Here’s an initializer generated by karafka generator with some extra tweaks:

# karafka.rb

# frozen_string_literal: true

ENV['RAILS_ENV'] ||= 'development'

ENV['KARAFKA_ENV'] = ENV['RAILS_ENV']

require ::File.expand_path('../config/environment', __FILE__)

Rails.application.eager_load!

# This lines will make Karafka print to stdout like puma or unicorn

if Rails.env.development?

Rails.logger.extend(

ActiveSupport::Logger.broadcast(

ActiveSupport::Logger.new($stdout)

)

)

end

class KarafkaApp < Karafka::App

setup do |config|

config.kafka.seed_brokers = %w[kafka://127.0.0.1:9092]

config.client_id = "karafka_example"

config.backend = :inline

config.batch_fetching = false

# Uncomment this for Rails app integration

# config.logger = Rails.logger

end

# Comment out this part if you are not using instrumentation and/or you are not

# interested in logging events for certain environments. Since instrumentation

# notifications add extra boilerplate if you want to achieve max performance,

# listen to only what you really need for a given environment.

Karafka.monitor.subscribe(Karafka::Instrumentation::StdoutListener)

Karafka.monitor.subscribe(Karafka::Instrumentation::ProctitleListener)

consumer_groups.draw do

consumer_group :example do

batch_fetching false

topic :users do

consumer UsersConsumer

end

end

end

end

Karafka.monitor.subscribe('app.initialized') do

# Put here all the things you want to do after the Karafka framework

# initialization

end

KarafkaApp.boot!

The most interesting parts of that file are configuration and drawing the routes, so let’s focus on them now.

In the configuration block, we need to specify URI for Kafka, which is going to be kafka://127.0.0.1:9092 by default (assuming that you have Kafka installed in the first place). We also need client_id to identify the app in Kafka and provide the proper namespace. Another option is specifying backend which we have set to be inline. It means that the processing of the events will happen in the karafka’s workers, which might not be an optimal solution, especially for heavy processing. Alternatively, we can use Sidekiq thanks to karafka sidekiq-backend gem. Keep in mind though that with Sidekiq backend the the messages might no longer be processed in the order they arrived! For the sake of simplicity and the demonstration purposes, batch_processing is set to false. In such case, instead of dealing with a batch of messages (that would be available under params_batch method), we are going to have just params representing a single message.

In the next section, we are configuring the equivalent of routes for Kafka. We are registering example consumer group under which we specify that we want UsersConsumer class to be the consumer for users topic.

Consumers group is a concept that allows having competing consumers pattern for messages, which is useful if you don’t want to have a publish-subscribe pattern with all consumers receiving the same message but only a single consumer processing the event.

There are a couple of more configuration options for topics that you can check in the docs.

Building a producer

Let’s build the simplest possible producer that will merely take the payload and publish it to users topic:

# app/responders/users_responder.rb

class UsersResponder < ApplicationResponder

topic :users

def respond(event_payload)

respond_to :users, event_payload

end

end

Building a consumer

And now, we can build a simple producer that will do nothing more than logging the params. As mentioned before, we have params method accessible on the instance level (or params_batch if batch fetching is enabled):

# app/consumers/users_consumers.rb

class UsersConsumer < ApplicationConsumer

def consume

Karafka.logger.info "New [User] event: #{params}"

end

end

Seeing things in action

Let’s start the server process:

bundle exec karafka server

If everything goes fine, you should see an output like this:

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:41.517728 #83821] INFO -- : Initializing Karafka server 83821

Karafka framework version: 1.3.0

Application client id: karafka_example

Backend: inline

Batch fetching: false

Batch consuming: false

Boot file: /path/to/app/karafka.rb

Environment: development

Kafka seed brokers: ["kafka://127.0.0.1:9092"]

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:41.602016 #83821] INFO -- : Running Karafka server 83821

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:41.602870 #83821] INFO -- : New topics added to target list: users

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:41.602948 #83821] INFO -- : Fetching cluster metadata from kafka://127.0.0.1:9092

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:41.798673 #83821] INFO -- : Discovered cluster metadata; nodes: your-machine-name.local:9092 (node_id=0)

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:41.798965 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] Will fetch at most 1048576 bytes at a time per partition from users

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:41.799144 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] Fetching cluster metadata from kafka://127.0.0.1:9092

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:41.799005 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] Joining group `karafka_example_example`

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:41.801184 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] Discovered cluster metadata; nodes: your-machine-name.local:9092 (node_id=0)

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:41.801287 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] There are no partitions to fetch from, sleeping for 1s

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:42.047094 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] Joined group `karafka_example_example` with member id `karafka_example-612b6612-26f1-41fe-95cd-49a52a6275c7`

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:42.047186 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] Chosen as leader of group `karafka_example_example`

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:42.803209 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] There are no partitions to fetch from, sleeping for 1s

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:43.050550 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] Fetching cluster metadata from kafka://127.0.0.1:9092

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:43.052574 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] Discovered cluster metadata; nodes: your-machine-name.local:9092 (node_id=0)

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:43.106051 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] Partitions assigned for `users`: 0

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:43.805927 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {users: 0}:] Seeking users/0 to offset 0

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:43.806048 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {users: 0}:] New topics added to target list: users

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:43.806083 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {users: 0}:] Fetching cluster metadata from kafka://127.0.0.1:9092

I, [2019-04-07T10:30:43.807502 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {users: 0}:] Discovered cluster metadata; nodes: your-machine-name.local:9092 (node_id=0)

And let’s send some dummy event from the console using UsersResponder:

rails console

UsersResponder.call({ event_name: "user_created", payload: { id: 1 } })

The output of that command should be similar to the following one:

I, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.216585 #84497] INFO -- : New topics added to target list: users

I, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.216940 #84497] INFO -- : Fetching cluster metadata from kafka://localhost:9092

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.217337 #84497] DEBUG -- : [topic_metadata] Opening connection to localhost:9092 with client id delivery_boy...

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.220633 #84497] DEBUG -- : [topic_metadata] Sending topic_metadata API request 1 to localhost:9092

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.221051 #84497] DEBUG -- : [topic_metadata] Waiting for response 1 from localhost:9092

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.222211 #84497] DEBUG -- : [topic_metadata] Received response 1 from localhost:9092

I, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.222554 #84497] INFO -- : Discovered cluster metadata; nodes: your-machine-name.local:9092 (node_id=0)

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.222818 #84497] DEBUG -- : Closing socket to localhost:9092

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.227719 #84497] DEBUG -- : Current leader for users/0 is node your-machine-name.local:9092 (node_id=0)

I, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.228077 #84497] INFO -- : Sending 1 messages to your-machine-name.local:9092 (node_id=0)

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.228535 #84497] DEBUG -- : [produce] Opening connection to your-machine-name.local:9092 with client id delivery_boy...

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.445056 #84497] DEBUG -- : [produce] Sending produce API request 1 to your-machine-name.local:9092

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.452673 #84497] DEBUG -- : [produce] Waiting for response 1 from your-machine-name.local:9092

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.507604 #84497] DEBUG -- : [produce] Received response 1 from your-machine-name.local:9092

D, [2019-04-07T10:33:31.507995 #84497] DEBUG -- : Successfully appended 1 messages to users/0 on your-machine-name.local:9092 (node_id=0)

=> {"users"=>[["{\"event_name\":\"user_created\",\"payload\":{\"id\":1}}", {:topic=>"users"}]]}

And if you check the logs of the karafka server, you will see that the message was successfully processed, including logging the message:

I, [2019-04-07T10:33:33.348308 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] New [User] event: {"create_time"=>2019-04-07 10:33:31 +0200, "headers"=>{}, "is_control_record"=>false, "key"=>nil, "offset"=>0, "deserializer"=>#<Karafka::Serialization::Json::Deserializer:0x00007fd463e96dc8>, "partition"=>0, "receive_time"=>2019-04-07 10:33:33 +0200, "topic"=>"users", "payload"=>{"event_name"=>"user_created", "payload"=>{"id"=>1}}, "deserialized"=>true}

I, [2019-04-07T10:33:33.348375 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] Inline processing of topic users with 1 messages took 9 ms

I, [2019-04-07T10:33:33.348410 #83821] INFO -- : [[karafka_example_example] {}:] 1 message on users topic delegated to UsersConsumer

And that’s it! That’s all that it takes to use Kafka in your Rails application.

What about other features?

We only used a tiny part of the framework, which turned out to be sufficient for the demonstration purposes. However, there are way more features that would be worth getting familiar with before using karafka in your application.

Summary

Kafka is a great tool if you want a reliable and performant way of sending events between applications where a persistent storage for a certain amount of time and an ability of replaying events is essential and/or if you plan to do heavy stream-processing. Thanks to frameworks like karafka, it’s quite simple to start using Kafka in Rails applications.