The inherent unreliability of after_commit callbacks and most service objects' implementation

Service objects and/or after_commit callbacks are ubiquitous in most real-world Rails applications. Whether it’s a good idea or not (ActiveRecord callbacks - I’m looking at you) is a different story, but one thing that is notoriously overlooked in the application design is reliability. And yes, the service objects are equally bad as after_commit callbacks in that regard.

Let’s explore the concept of reliability and also some solutions that can help solve the problem.

Using transactions and reliability

Typically, after_commit callbacks are used for executing side effects after the transaction. And for a good reason! This is usually where some background jobs are scheduled, and it would be pointless to do that from, for example, the after_save callback as the transaction can fail. In such a scenario, the background job will never be processed and will keep failing with the ActiveRecord::RecordNotFounderror. So using after_commit sounds like a great design decision, right? Right..?

Unfortunately - no. Let’s make this problem even more apparent with a simple service object:

class UserCreator

def call(params)

user = User.new(params)

if user.valid?

ActiveRecord::Base.transaction do

user.save!

UserProfile.create!(user: user)

end

UserCreatedNotifierJob.perform_async(user.id)

MySuperCriticalJobThatAbsolutelyNeedsToBeExecuted.perform_async(user.id)

else

raise ActiveRecord::RecordInvalid.new(user)

end

end

end

There is nothing special here, and at first glance, it might actually look quite solid - there is a transaction block for two separate writes, so either both will succeed, or both will fail so that the state will be consistent. And also, the side effects are outside the transaction block, and they happen after the commit, just like after_commit.

So what’s the problem here?

There is no guarantee that anything after the transaction block will be executed. As far as the transaction goes, this is entirely clear - it will just work as you expect. However, once the transaction ends, there is a chance that the rest of the logic might just not be executed. And exactly the same thing applies to after_commit callbacks.

The process might experience Out Of Memory error and will be killed right after the transaction block. It might also be restarted, or maybe the node where the actual process is running might be taken down. There are multiple ways how it can happen. It doesn’t mean that it happens often, it’s more of a relatively rare edge case, but on a huge scale, even the low-chance events can happen multiple times per day. And it would be pretty bad if MySuperCriticalJobThatAbsolutelyNeedsToBeExecuted was not executed 100% of the time.

The key question to ask at this point would be: what’s the solution to that problem? For sure, moving the execution of the side effects to the transaction block is not the solution. Having some errors in the background jobs is definitely the least problematic scenario you could experience.

Imagine performing some HTTP requests that modify the state in some external service. If the transaction failed, an automatic rollback handled by ActiveRecord wouldn’t be enough - you would also need to execute some compensatory logic on the third-party service, which not only brings massive complexity, but it might also be not easily doable - for example, if that service delivers some notifications, e.g., SMS message or even just sends an email.

Fortunately, there is a well-established pattern precisely to this problem. It’s a transactional outbox.

Transactional Outbox Pattern

The transactional outbox pattern is based on the atomicity of the transactions (and no, we don’t need a distributed transaction here) - either everything fails or everything succeeds.

To apply this pattern, we need to create something extra in the transaction - a dedicated Outbox Entry record that will stand for the execution of some side effects. Then, some external process will fetch it, execute the side effects, and mark the entry as processed (or destroy the record to not re-execute it again in the future).

Essentially, it would be using an ACID database as a temporary message queue.

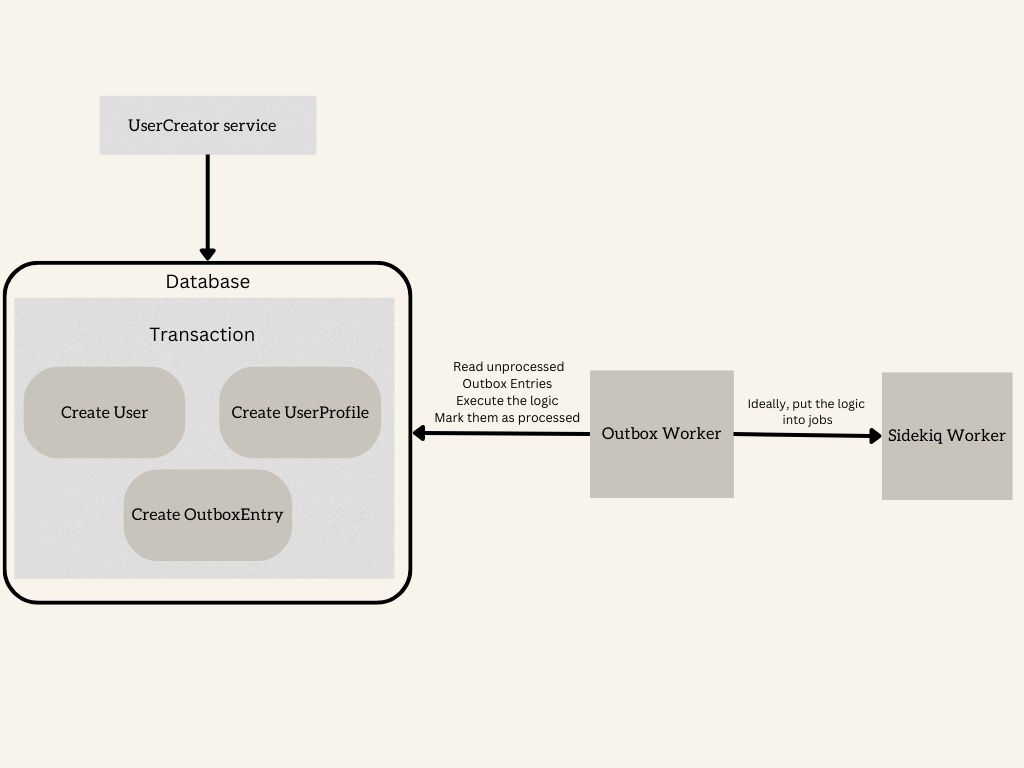

Here is how we could visualize the entire flow:

As the graph shows, theUserCreator service creates all the records within the same transaction, including the OutboxEntry. Later, some Outbox worker (a separate process) picks unprocessed records (probably in the infinite loop), executes the logic (ideally, scheduling Sidekiq jobs where the actual side effects will be executed), and marks the entries as processed so that the records will not be processed again in the next iteration. It’s important to keep in mind that it will likely imply the at-least-once delivery semantics as the process might get killed after scheduling jobs (but right before marking entries as processed), so the jobs need to be idempotent. Funny enough, that’s another potential reliability issue inside the solution that is supposed to bring more reliability.

The unclear part is how exactly the Outbox worker will know what logic to execute once it fetches the entries. The essential thing is that the entry itself should contain some indicators. It could be, for example, the event name with the ID and name of the created model (so here: “user_created” event with “User” as model_class and its ID as model_id) and based on that, you could implement some pub-sub mechanism using model class and its ID as arguments. Or you could store the name of the service instead of the event name and implement some dedicated method/hook, like on_success that would be executed by the worker:

class UserCreator

def self.on_success(user)

UserCreatedNotifierJob.perform_async(user.id)

MySuperCriticalJobThatAbsolutelyNeedsToBeExecuted.perform_async(user.id)

end

def call(params)

# original method goes here

end

end

Using events might be a bit more complex, but it can sometimes be worth it. One of the significant benefits is that such a solution will make it easier to use event sourcing in the future or at least have an event-driven architecture.

We’ve managed to cover service objects, but what about after_commit callbacks? Ideally, you would not use them at all. However, if there are already there in the app and the refactoring/rewrite is not feasible, there are some things that you could do that are not that complex.

First, you would need to use some other dedicated callback that would work like after_commit but would not be a part of ActiveRecord, for example, a custom reliable_after_commit that would have the same interface as after_commit. The next step would be to keep these callbacks in some registry accessible from the outside (like Model.reliable_after_callbacks) so that the worker can easily execute each of them. And since after_commit callbacks often contain some logic taking advantage of dirty-tracking (previous_changes), you would also need to store such changeset with the Outbox Entry and bring back that state in the Outbox worker when materializing the model record.

Sounds complex? Fortunately, you don’t need to implement this logic or even the worker itself. You can use rails-transactional-outbox gem that I extracted from one of the BookingSync projects as an experimental way of addressing reliability concerns.

Conclusions

Reliability is a factor that is arguably often overlooked when it comes to implementing business logic, at least if judging it by the popularity (or lack of it) of a transactional outbox pattern or other alternatives. Fortunately, the pattern itself is not very complex, and some solutions are available as gems that make it easy to apply the pattern in your Rails applications.